By Catherine McBride – 7 minute read

IF LIZ WEBSTER didn’t exist, would anyone invent such an entitled self-important nitwit?

For those who don’t know her, Liz Webster is a keyboard warrior who claims to be a farmer, although in 2019 she ran a recruitment agency placing nannies and household staff with families. Those of us (and there are many) who know real farmers also know they do not have the time to sit on Twitter all day and give interviews on TV and radio, all demanding the UK re-join the EU.

Nevertheless, her recent attack on Namibian beef exports is really beyond the pale.

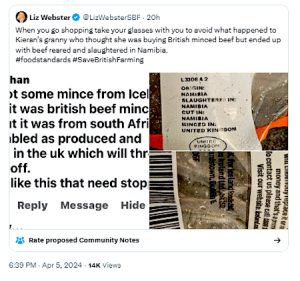

Webster’s highly visible ignorance of real life in Britain as well as food standards and trade agreements was again on display when she posted on Twitter, “Global Britain means risking your life every time you eat” after reading the label on some supermarket minced beef that clearly stated the beef was from Namibia but minced and packaged in the UK.

So how was this life-threatening? The UK has a trade agreement with Namibia; it is a continuity agreement rolled over from the EU’s trade agreement with the Southern African Customs Union and Mozambique. That means Webster’s precious EU also has a trade deal with Namibia, and the same process and packaging would have been possible before Brexit.

It is shocking how little the British middle class knows about the rest of the world’s food and agricultural standards. They also seem to know nothing about the work of the UK’s Food Standards Agency which regulates and ensures UK food safety, hygiene and standards – including protecting us from dodgy food and food ingredients from the EU. It is an irrefutable fact that the food scares of horse meat in Irish-made burgers (2012) for Tesco, Dunnes Stores, Aldi, Lidl and Iceland – and the avian flu in turkeys from Hungary appearing in British Turkey farms (2007) happened while we were inside the EU. And when there were no border checks on imported EU food, as there will be from today.

This lack of knowledge appears to be worst amongst EU Re-joiners like Webster. They have been telling themselves the UK has the ‘highest framing standards in the world’ for so long, they have started to believe it. But it just isn’t true. UK farming standards are fine, but they were designed to suit European farming practices and their outcomes are no better than many other food-exporting countries. And if you prefer solely grass-fed beef, then UK standards are probably not as good as many countries with more temperate climates, such as Namibia.

Webster and her followers will probably be surprised to discover the Namibian meat processing and marketing company, Meatco, not only has a subsidiary in the UK, the Meat Corporation of Namibia (UK) Ltd, but that its Windhoek Abattoir is compliant with the British Retail Consortium Global Standards (BRC) and with the FSSC 22000 (Food Safety System Certification). The BRC measures ethical and fair practices, animal welfare and corporate social responsibility and has apparently awarded the Windhoek Abattoir a BRC ‘A’ grading. Namibian beef is not only exported to the EU, Norway and the UK, it is also approved for export to the US and China – all of which have tough food regulations and controls.

Namibian cattle live on veld grass and are not given growth hormones or routine antibiotics, nor are they kept in sheds during the winter like we do in Britain. Meatco’s flagship Nature’s Reserve label is ISO, HACCP and Halal certified and can be traced back to the farm of origin. So why does Webster believe she would be risking her life if she ate Namibian beef?

Unfortunately, this is not an uncommon attitude amongst the hysterical middle-class protectionists who helped kill a UK-US trade deal with their irrational fears of US chicken meat washed in water containing either Choline Dioxide or Peracetic Acid to kill bacteria. Besides the fact the same process is used to wash ready-to-eat salad leaves in the UK and chlorine is put into UK and EU drinking water, the UK is mainly self-sufficient in chicken meat so it was unlikely any US chicken would have ever been imported had we agreed a general trade deal.

A trade deal with the US could, however, have provided a valuable new market for British sheep farmers. The US imports between 120,000 and 170,000 tonnes of sheepmeat each year, almost all of it from Australia and New Zealand as, unlike the UK, they both have trade deals with the US. Importantly, and to our advantage, their lambing season is the opposite of the UK’s so they would not have been in direct competition with UK lamb in the US market.

Meanwhile, the hysterical protectionists happily eat anything from any EU country, mistakenly believing all EU countries have the same farming rules as the UK – but they don’t. Even within the UK, each home nation has its own rules, as agriculture has been a devolved matter since at least 1997.

I have also found the ‘food standards’ that UK shoppers may be interested in, for example, the presence of E.coli, are generally not the ‘standards’ imposed on British farmers and the basis for the claim of ‘the highest standards in the world’ – for example, whether a farmer can dock a pig’s tail and how much light must be provided for animals housed in a shed.

Why we should be trading with Namibia

Namibia is a large but extremely dry country on the west coast of Southern Africa, it is home to the Skeleton Coast, popular with well-heeled British tourists (some of whom are probably hysterical protectionists). Its economy is dependent on trade: exporting diamonds, uranium, copper, gold, zinc, lead, fish fillets and meat – and importing oil, chemicals, vehicles and mining equipment.

Namibia’s GDP per capita was estimated to be $4,786 in 2023 by the IMF. The IMF estimates the UK’s GDP per capita to be $48,912 in 2023, so over 10 times that of Namibia. However, although Namibia’s GDP per capita is relatively high compared to many African countries, its GDP is not evenly distributed and the World Bank estimates Namibia’s Gini coefficient was 0.591 in 2015, the second highest in the world. Gini coefficients technically range between zero – perfect equality, to 1 – perfect inequality; although in practice they range between 0.2 and 0.6. (The UK’s Gini coefficient was 0.326 in 2020.)

While Namibia’s mineral wealth will mainly accrue to large companies and the government, for example, Namibia’s diamond industry is a joint venture between DeBeers and the Namibian government, while its uranium mines are either entirely owned or majority-owned by Chinese companies. Importantly, however, the revenue gained from Namibia’s exports of fish and meat will have a greater impact on the incomes of individual farmers and fishermen – real communities. Most of the Namibian population is employed in the agricultural sector either directly or indirectly. Livestock farming is worth about N$6.3 billion (£270 million) to the Namibian economy. To put that into perspective, the UK subsidised its farmers to the tune of £3.7 billion in 2022. Yet still, keyboard warriors like Liz Webster promote fear of cheaper imports from Namibia, Australia, New Zealand and anywhere other than the also subsidised EU.

According to ITC COMTrade, Namibia exported 6,682 tonnes of frozen beef in 2022 (the most recent statistics available from Namibia) and 3,076 tonnes of fresh beef. But its largest agricultural export is Chicken – exporting 43,588 tonnes in 2022. Webster may be surprised to know that Namibia’s largest frozen beef export market in 2022 was EU member Netherlands, then South Africa, then China. The UK was Namibia’s 4th largest frozen beef market in 2022, importing a mere 633 tonnes. Although in 2023 our UK records show we imported almost 1,600 tonnes of Namibian frozen beef.

Ironically, the UK imported much greater quantities of Namibian beef when it was a member of the EU: in 2013 we were their 2nd largest export market after South Africa, importing 3,087 tonnes of frozen Namibian beef. No doubt, the hysterical protectionist Webster, will be horrified by this news. But If Namibian grass-fed beef was good enough for us when we were EU members, surely, we can help out Namibian farmers now?

The average UK import price for frozen beef from Namibia was 20% less expensive in 2023 than the average import price for frozen Irish beef, the UK’s largest supplier, including transport costs. (ITC COMtrade figures) Import prices include cost, insurance and freight (cif). Interestingly, Webster didn’t show the price of the minced beef she bought in Iceland in her Twitter post, but we can assume it was less expensive than UK or Irish beef which must have sparked her outrage.

Importing Namibian beef not only helps poor Namibian farmers trying to make a living out of exporting livestock, but it is also helping the many UK consumers who find the current extraordinarily high price of meat in the UK out of their budgets.

Self-obsessed Webster probably knows nothing of life for those on a below-average income in Britain, just as she knows nothing about international farming standards nor of the work of the UK’s Food Standards Agency, so please stop listening to her.

If you appreciated this article please share and follow us on Twitter here – and like and comment on facebook here. Help support Global Britain publishing these articles by making a donation here.

Catherine McBride is an economist and the author of Brexit and UK trade – What has changed? a paper analysing UK trade performance by sector since Brexit. She is a member of the Government’s Trade and Agriculture Commission.

African cattle on the veld by Phoebe via Adobe Stock