WHILE MOST PEOPLE are worried about coming shortages: fuel, food and even water, there are still some members of the Twitter fraternity worried about surpluses. Specifically gluts of agricultural products – or what most of us would call ‘food’ – being imported into the UK from Australia and New Zealand.

Increased supply of food usually lowers prices, and as the UK is presently facing a ‘cost-of-living- crisis’ which includes higher food prices, then surely it should be a good thing the UK will have ample supplies of food, if not fuel, from countries unaffected by the present supply-chain disruptions in Europe?

Alas, some people would prefer the UK remains dependant on the EU for its food even though with fuel shortages, drought (yes, the EU has a water shortage as well), high fertiliser prices and some EU countries’ own crazy Net Zero Agendas, the UK relying on the EU for food may soon look as foolish as Germany relying on Russia for fuel.

Each year the UK consumes over 1 million tonnes of beef of which over 300,000 tonnes is imported. Most of these imports, over 90%, come from Ireland. Likewise, the UK’s largest supplier of fruit and vegetables is the Netherlands. You may be thinking Ireland and the Netherlands are nothing like Russia, why would our supply of food be in danger? But you may have missed the summer news stories: The Netherlands is requiring its farmers to cut nitrogen emissions by 50% by 2030 which will necessitate a 30% reduction in farm animals while Ireland is apparently planning to cull its cattle herd in order to meet its Sectorial Emissions Ceiling by cutting its carbon emissions by 25% by 2030.

The Irish Minister for Agriculture, Charlie McConalogue, has denied meeting this target would require forcing a reduction (culling) of 13% of Ireland’s beef herd and 11% of its dairy herd. Let’s hope this is true as the UK relies on imports of Irish beef, butter and cheese to feed its ever expanding (mainly immigrant) population.

It is surprising the Irish government is requiring these cuts, as nothing Ireland does to its carbon emissions will change international greenhouse gas emissions. Ireland is only responsible for 0.1% of global emissions now and by 2030, if China and India increase their emissions as planned, Ireland’s emissions may be back to its pre-1920 levels of only 0.01%. But hey, it’s the thought that counts when you are virtue signalling.

Unfortunately for Irish farmers (and the people of the UK who rely on food imported from Ireland), agriculture is by far the biggest CO2 emitter in Ireland, producing 40% of total emissions – more than the transport and electricity and heating sectors combined. Also, since 1990 Ireland’s electricity and heat sector emissions have dropped by 14%, while agricultural emissions have increased by 5%. So, despite providing employment to 8.5% of Ireland’s population, creating 10% of Irish goods exports, agriculture is the sector where Irish politicians will be able to gain some Green street-cred with their EU mates. And the easiest way to do this will be by culling cattle herds – even though it makes zero difference to global emissions.

So, should the UK worry? Well, some might imagine our new trade agreements with Australia and New Zealand will be able to make-up for any lost imports of beef, cheese and butter from Ireland. Afterall Australia is one of the world’s major beef exporters, as is New Zealand for dairy products.

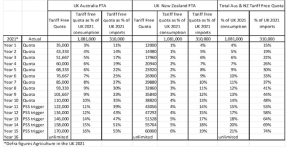

But no, our trade deals keep us reliant on EU supplies of meat for at least 16 years more, and cheese and butter for at least 5 years. Outside of the small tariff free quotas, beef imported from Australia and New Zealand will still be subject to the UK’s full Most Favoured Nation (MFN) tariffs for 10 years and then have 20% tariffs applied on import quantities over the Product Specific Safeguard (PSS) limits for another 5 years. (This is a safeguard for UK and EU producers, not UK consumers.)

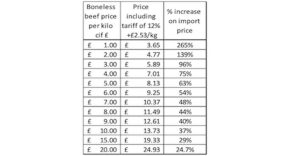

The UK’s MFN tariffs on beef are so high little to no meat is imported outside the tariff free quota. For example, Fresh or Chilled Boneless Beef has a tariff of 12% plus £2.35 per kg. This means chilled boneless beef landed in the UK for £1 per kilo, would cost £3.65 including MFN tariffs, a 265% increase in its price; £2 per kilo beef would cost £4.77, a 139% increase; £3 per kilo beef would cost £5.89, at 96% increase, etc.

Obviously the more expensive the imported beef the smaller the percentage tariff. The tariff on chilled boneless beef costing £10 per kilo would add 37% to the price, while the tariff on boneless beef costing £20 per kilo would add 25%. Of course, we are talking about wholesale prices so £20/kg beef would be a very expensive cut or very high-quality beef.

The five-year average price of chilled or frozen beef imported from Ireland was only £4.43. Not because Irish beef is very cheap (although it is about 20% cheaper than UK beef) but because we import everything from mechanically removed mince from old dairy cows to the best fillet steak. While the five-year average price of imported chilled beef from Australia was £7.58/kg reflecting the tariff structure that makes importing cheaper cuts of beef from Australia uneconomic.

So how much beef will we be allowed to import from Australia and New Zealand under the new trade deals? Not very much compared to UK consumption or UK imports from Ireland.

In the first year the trade deal is in force, the tariff free quota for Australia will be 35,000 tonnes, about 3% of UK consumption while New Zealand beef imports will be limited to only 12,000 tonnes, about 1% of UK consumption.

Even in 15 years, 2038, the amount of tariff free beef consumers in the UK could buy from Australia and New Zealand will be only just over a fifth of the UK’s 2021 consumption and about three quarters of the UK’s 2021 beef imports of 310,000 tonnes. If, however, the population grows between now and 2038, then much larger amounts of imported beef would be required.

So where will this come from? Probably not Ireland or the Netherlands as they will have reduced their cattle herds.

The moral of the story is don’t rely on a single supplier or a small group of suppliers with the same weather and emission targets to supply essential products such as food or fuel. And if you believe UK farmers could increase their own cattle herds to supply increased domestic demand without imports, without increasing their emissions, all while retaining their apparently gold-plated animal welfare regulations, then why haven’t they done so before?

Catherine McBride is an economist who writes about Trade and agriculture. She is on the Government’s Trade and Agriculture Commission and is a fellow of the Centre for Brexit Policy.

Catherine McBride

15 August 2022