by Cormac Lucey

IN THE WAKE of the Good Friday/Belfast agreement, routine border checks between Newry and Dundalk disappeared. That disappearance rested on two foundation stones: peace in Northern Ireland, and the fact that the north and the Republic were both members of the EU single market and customs union. That second foundation stone is now to be whipped away as the UK exits both. When Theresa May, the British prime minister, famously stated — and then repeated — the line “Brexit means Brexit”, she really meant “Brexit means hard Brexit”.

By opting upfront for a hard Brexit, the British government may be presenting EU policymakers with an appalling vista and thereby inviting them to respond with a counter-proposal. For while, in the short term, Britain would undoubtedly be hit worst by the multiple dislocations triggered by a hard Brexit, it does not face the same existential threat facing the eurozone.

The grandiose but incomplete European economic and monetary union project features Greece and Italy hanging on grimly even as their debt levels rise from the unsustainable to the absurd. Spain and Portugal are running to stand still. Elsewhere, political revolts are brewing across the eurozone. It all begs the question of what Ireland’s stance should be.

This country has had the perfect opportunity to develop economically and politically since 1973, when both ourselves and Britain joined the European Economic Community, the forerunner of the European Union. For several decades the UK — the entity with which we have the closest human and business links — and the EU — the entity with which we have the closest political and institutional links — have been operating in broad harmony. But now they are going their separate ways.

Today Ireland is like a child whose parents are separating. Whatever reassuring noises the parents may make, that split will inevitably come with a cost and pose difficult questions. Northern Ireland will face a similar problem as the British and Irish governments get pulled in separate directions by the Brexit fallout.

To date, the Dublin establishment has kept its head down, hoping that public fealty to the European ideal will win favour in Europe. But this is to place faith in an EU establishment that may not have Ireland’s best interests at heart, if the European Commission’s €13bn Apple tax liability decision means anything.

It is notable that when taoiseach Enda Kenny travelled to Berlin last summer to persuade his friend the German chancellor Angela Merkel that Ireland should be seen as a special case in the Brexit negotiations, he travelled home empty-handed. In 1916 the Irish Citizen Army paraded in front of Liberty Hall draped in the banner, which proclaimed: “We serve neither king nor kaiser, but Ireland.” Did Ireland achieve its independence from the king and his successors just to hand it over to the heirs of the kaiser?

It is also notable that the official response to Brexit has been of the “calm down and don’t worry” nature. The Irish Independent recently reported that Revenue officials had “encouraging” talks with the European Commission about the future of border checks. It was stated that officials had visited the borders between Switzerland and Austria and Sweden and Norway to gather ideas. All very reassuring.

But both Switzerland and Norway are members of the EU’s single market, which Britain intends to leave. While it is comforting that Irish officials are making efforts to learn from the experience of others, it is perplexing that they are learning from examples with such limited applicability.

To see what Ireland might face in the future, Revenue officials might have been better off travelling to Poland’s borders with Russia. Or they could have popped out to Dublin airport to see how their colleagues already handle traffic with America.

The dog that has hardly barked in this debate is the question of Ireland’s continued membership of the EU. Polite society — the government; big political parties; main media outlets; business group Ibec; trade union association Ictu; and the state’s epicentre of pro-EU sentiment, the Institute of International and European Affairs — take it as read that Ireland’s membership of the EU should continue despite Britain’s impending exit.

The former Irish diplomat Ray Bassett has argued: “The present instruction is that, at all costs, no indication can be given by our officials that our continued membership of the EU is in any doubt, regardless of the outcome of negotiations on Brexit. The policy is very much at odds with our national interest.”

So can a strong argument for an Irexit be made? In my opinion it can.

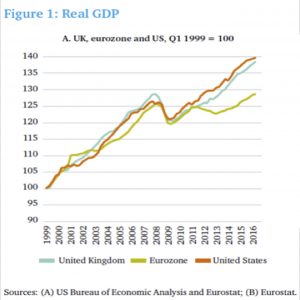

The key argument against continuing EU membership is that the whole of the EU is so far less than the sum of its parts. Since the eurozone crisis erupted nearly a decade ago, economic growth in the EU has fallen far below its potential. Eurozone policymakers may want to kick the can down the road indefinitely but eventually they will run into a brick wall.

The EU’s efforts at a common foreign policy have been dogged by too much ambition combined with too little commitment in both Libya and Ukraine. The less said about the EU’s efforts at a common migration policy the better. The European Court of Justice is not so much a court as another institutional organ slowly and quietly turning the screw in favour of “ever closer union”, regardless of what voters indicate they actually want.

The EU may preach reconciliation but many of its own citizens hate it and its overbearing bureaucrats.

Of course, there are strong arguments for remaining within the EU. The most important is that Ireland’s success in attracting mainly US-owned foreign direct investment (FDI) depends to a considerable extent on our membership of the single market and the tariff-free access to European markets provided by membership of the customs union.

Paradoxically, the higher the EU’s external tariff walls, the greater Ireland’s attractiveness to US business. Exiting the EU could expose the FDI sector — from which more than a quarter of national economic output is derived — to grave peril.

Another argument for staying inside the EU is that if it didn’t exist, something very similar would have to be invented to replace it. How else are small nations in a declining continent to make any international impact in discussions on issues such as trade and global warming?

Furthermore, it can be argued, the EU simply isn’t going to become a federal superstate. The notion lacks the necessary political support to be realised. And wouldn’t leaving the EU together with Britain not just make us politically and economically dependent on our nearest neighbour again?

The arguments for Ireland leaving or remaining within the EU are more finely balanced than may be comfortable for the Dublin establishment. What is extraordinary is that so few of our influence-formers are even considering the question. To date Brexit has been met in Ireland by soft thinking. But hard Brexit may force us, against our will, to engage in some hard thinking.

We are indebted to Cormac Lucey for his permission to publish this article which first appeared on the Hibernia Forum.